The Minnesota Zoo Opens the Treetop Trail

The longest elevated pedestrian loop in the world is the culmination of a decade-long effort to transform the zoo’s shuttered monorail system

By Justin R. Wolf | August 17, 2023

A young visitor peers down from the Treetop Trail on its opening weekend. Photo courtesy of the Minnesota Zoo.

FEATURE

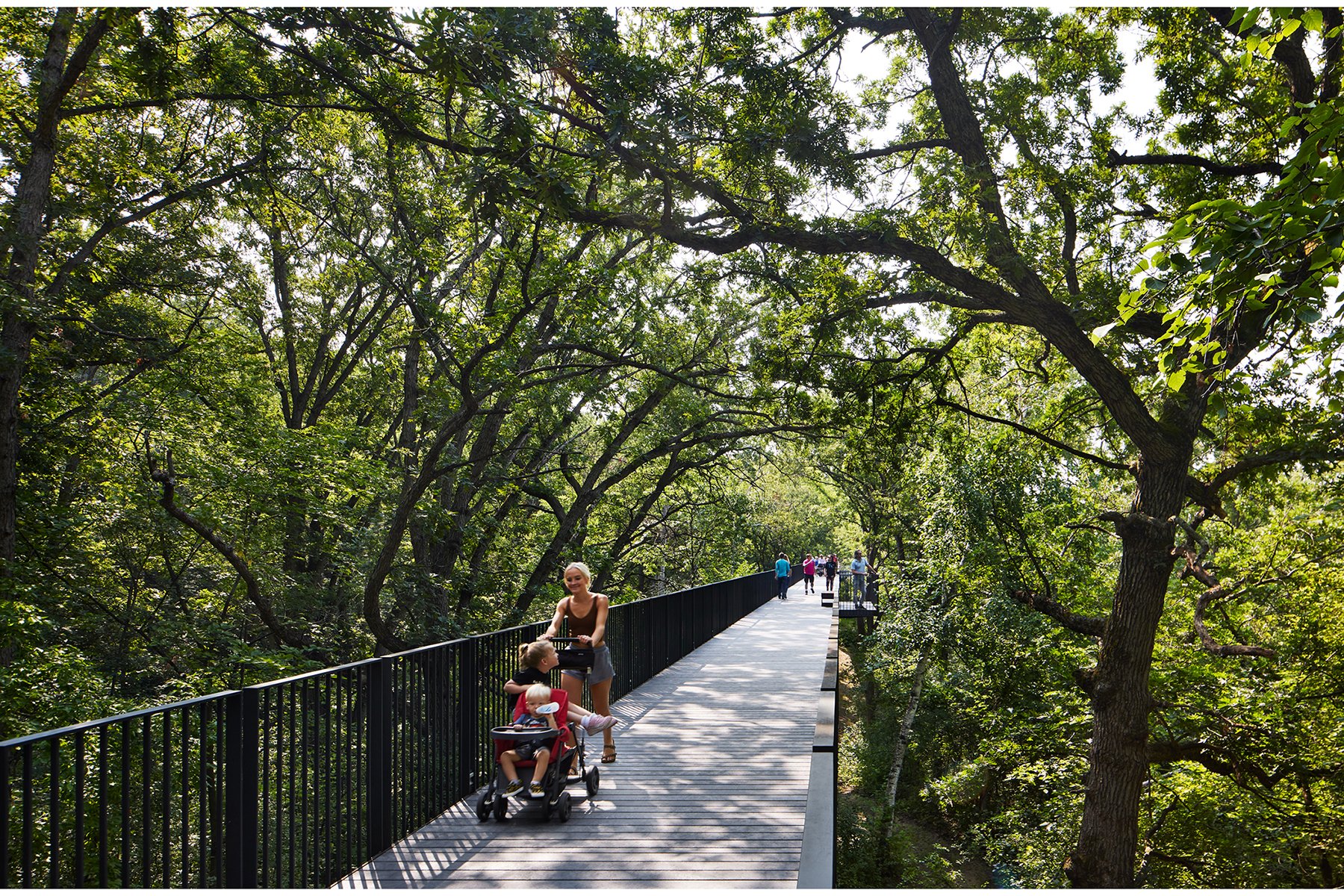

On July 28, World Nature Conservation Day, the Minnesota Zoo in Apple Valley unveiled a one-of-a-kind project that, depending on your point of view, had been either 10 years or several decades in the making. The Treetop Trail, designed by Snow Kreilich Architects and Ten x Ten, is a 1.25-mile, elevated pedestrian walkway that winds and stretches around the zoo’s Northern Trail section, taking visitors on a circuitous journey through the property’s varied landscapes, vistas, and canopies. Returning guests will recognize the structure: The trail is an adaptive reuse of Skytrail, the zoo’s monorail system, which was decommissioned in 2013 and had been plagued with financial and maintenance woes throughout its 34 years of operation.

The new trail offers visitors a “bird’s-eye view of many of the animals,” says Snow Kreilich’s Natalya Egon, AIA. The Minnesota Zoo was designed for this effect from the start. Although it’s hard to discern at ground level, much of the nearly 500-acre property resembles a large bowl with the depression centered around the Northern Trail, where bison, pronghorns, wild horses, and other species roam the grounds at select points. “The monorail was part of the original plan,” says Zach Nugent, the Minnesota Zoo’s interim director of marketing and communications. “The zoo was designed for aerial views of our large animal habitats, but for the past 10 years guests haven’t had that vantage point.”

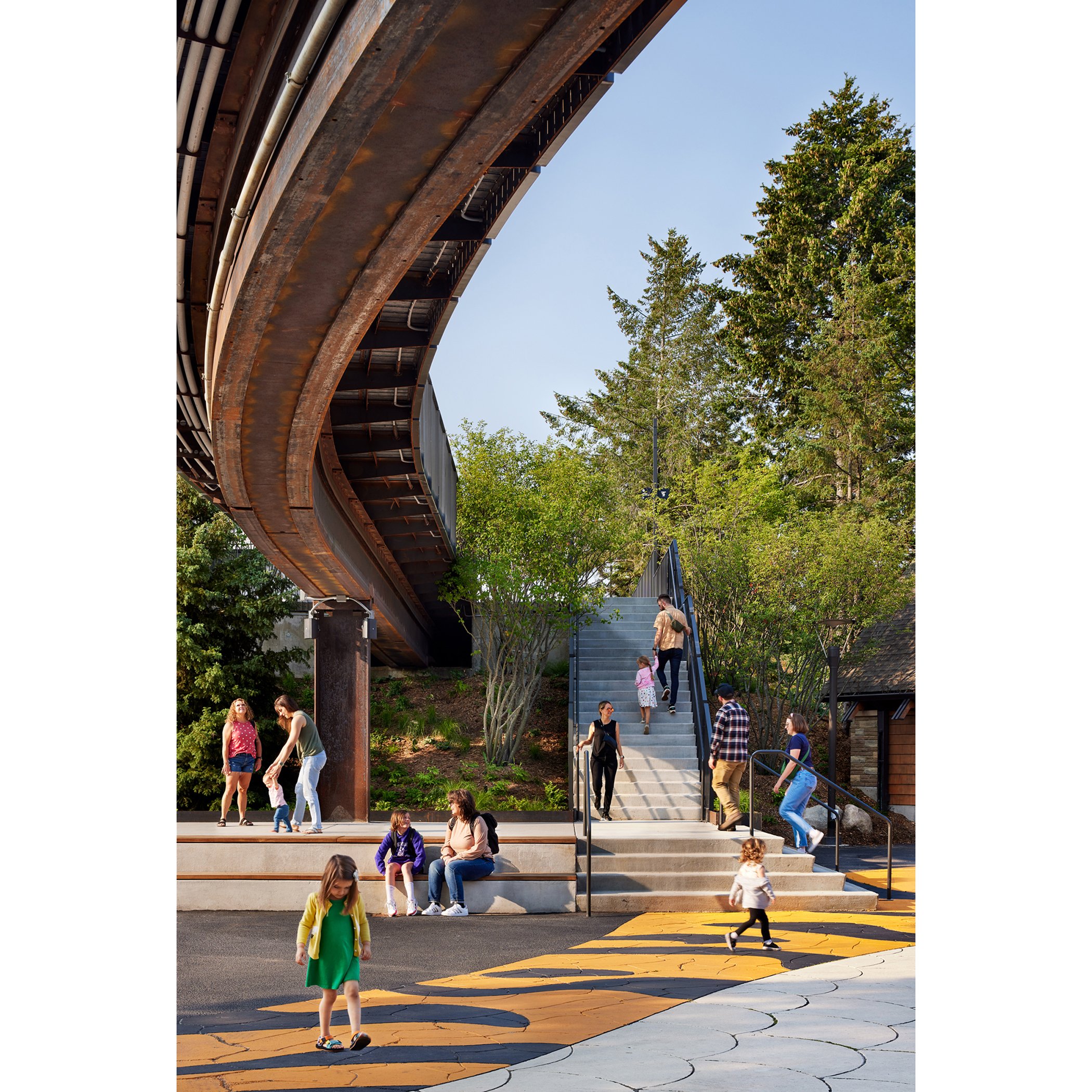

Images 1–13: Treetop Trail adjacent to existing ground circulation; Treetop Trailhead; through the landscape; Bison Landing; Hanifl Nature Center; Moose Landing; above the Tiger Exhibit; Reflection Pond Overlook; mix of existing and new materials; trail through the “North 40”; “Fire” Overlook; stair access to the trail in the Hanifl Nature Center; a walk in the woods. Photos by Gaffer Photography.

John Frawley was named director of the Minnesota Zoo in early 2016. Shortly after, on a trip to New York, he made a visit to the High Line, a conversion of a nearly mile-and-a-half-long stretch of an elevated rail structure on Manhattan’s West Side into a public park. Frawley couldn’t help but think of new possibilities for the shuttered monorail. That same year, the zoo commissioned Snow Kreilich Architects to lead a feasibility study for a pedestrian walkway conversion and began fundraising. The new Treetop Trail “broke ground” last year.

“We built in modular sections, with most of the work done from above so we didn’t disturb the habitats below,” says Paul Krienke, project superintendent with PCL Construction. Fortunately, the trail runs in between or around the animal habitats, apart from the bison area, which the trail passes over. Existing columns were reinforced and bracing was introduced to account for the substantial loads—both static and fluctuating—borne by an elevated walkway. “The whole continuous-loop steel trail structure expands and contracts up to four feet,” says Krienke. “All the fasteners and clips have those expansion and contraction capabilities, so everything moves together and there are no gaps or buckles.”

“The existing rail evoked a Richard Serra [sculpture] moving through the landscape. We wanted to respect its understated elegance and design a trail that was equally understated. It’s about allowing what surrounds you to be seen and experienced from there.”

“Repurposing the existing monorail structure required a close collaboration between Snow Kreilich and our structural engineers, Buro Happold and Meyer Borgman Johnson,” says Snow Kreilich’s Mary Springer, AIA. “Structural capacity, movement, twisting, and vibration were carefully considered at every design stage, from determining trail widths and bump-out locations to the smallest details of guardrail and trail connections, intersecting geometries, and attachments for interpretive signage.”

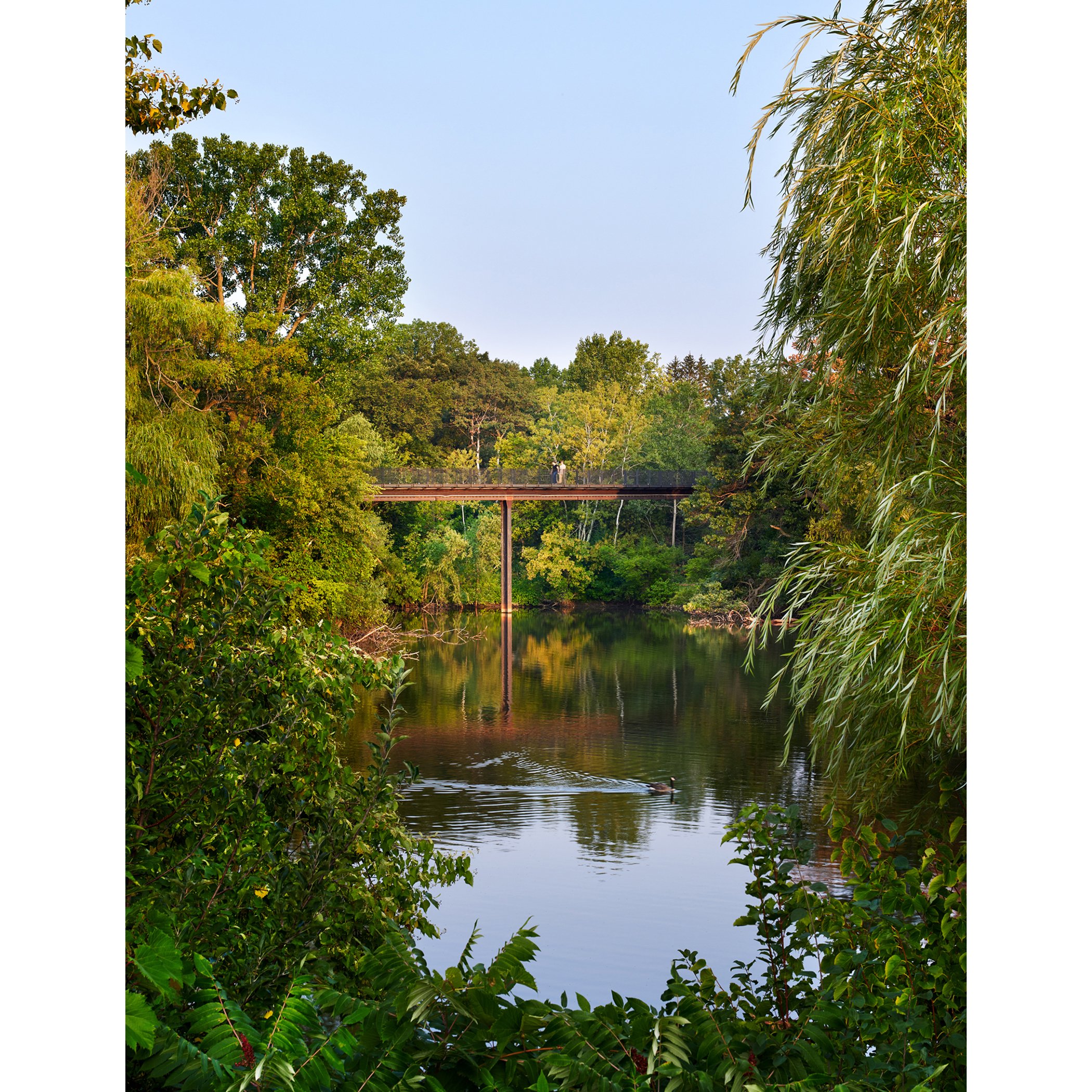

The eight-foot-wide trail is composed of the weathering steel structure, more than 15,000 recycled-plastic deck boards, and metal guardrails in four-foot sections that are bolted (not welded) at the base for easy removal. The path is complemented by pergolas, wood benches, downward lighting, IT connections, four new accessible on/off-ramps, and 24 strategically sited lookouts, where the trail widens.

The design is restorative and low impact at every scale. Building materials were regionally sourced: The steel was fabricated in Somerset, Wisconsin; the recycled boards came from Worthington, Minnesota; and Arbor Wood in Duluth supplied the wood for the pergolas and benches. Disturbances to the site caused during construction were offset by new native plantings and the removal of invasive plant species that had cropped up in the last 10 years.

Images 1–5: Through the landscape; steel underside of the trail; steel guardrail and thermally modified wood seating; bird-safe glazing; nature-based interpretive elements. Photos by Gaffer Photography.

“The back of house is now the front of house,” says landscape architect Ross Altheimer, principal and cofounder of Ten x Ten. Altheimer is referring to the northern portion of the grounds, which had become inaccessible to guests when the monorail closed. A major draw along this section of the path is the reflection pond, which the trail traverses. Here, the walkway includes a 90-foot-wide lookout. A wooden bird blind will be installed in the fall.

Reintroducing visitors to the zoo’s cultural landscape, old-growth woods, and wetlands is a key component of the organization’s wellness- and mobility-themed facilities master plan, dubbed “The Pathway to Nature.” “This trail had a life and presence,” says Altheimer. “So, we asked, ‘How do we carry that forward while honoring the zoo’s intent to offer an experience of the place from above?’” Part of the answer lies in the trail’s interpretive signage, which unfolds in a series of themes including Stewardship, Ways of Knowing Nature, Conservation, and Mindfulness.

Another part can be seen in the trail’s understated approach. “The existing rail evoked a Richard Serra [sculpture] moving through the landscape,” says Snow Kreilich’s Matthew Kreilich, FAIA. “We wanted to respect its understated elegance and design a trail that was equally understated. It’s about allowing what surrounds you to be seen and experienced from there.”

The Treetop Trail’s restorative nature extends to several of the zoo’s existing facilities. The monorail’s main ticketing area and on-ramp, which had become a proverbial bridge to nowhere, is now a landscaped entrance for the expansive trailhead, and the former Grain Elevator building has been completely redesigned as an exhibit space and additional access point for the trail, now known as the Hanifl Nature Center.

As a collection of movements and vistas, the Treetop Trail can elicit epiphanies even for the zoo’s most frequent guests. It leads patrons from one experience to the next, “honoring the trail’s natural path,” says Altheimer, but through an entirely new lens.

The Treetop Trail project team included Snow Kreilich Architects, Buro Happold, Meyer Borgman Johnson, Summit Companies, Ten x Ten, Victus Engineering, Barr Engineering, MIG, SIG, True North, and PCL Construction.