Mino-Bimaadiziwin Apartments

The story of a new community complex in the American Indian Cultural Corridor in Minneapolis

By Ann Mayhew | July 20, 2023

The courtyard includes a community gathering circle and a modern interpretation of a traditional medicine garden. Photo by Alan Blakely.

FEATURE

This feature expands on the Mino-Bimaadiziwin Apartments project gallery in the 2023 ENTER print annual.

When asked about the impetus for Mino-Bimaadiziwin Apartments—a multiuse affordable housing complex in Minneapolis developed by Red Lake Nation and designed by Full Circle Indigenous Planning + Design with Cuningham—Ojibwe architect Sam Olbekson, AIA, AICAE, NOMA, quips, only half-jokingly, “It all started in 1492.”

Although Mino-Bimaadiziwin is a single building, it has, from its outset, been a part of a broader context of projects and communities in the American Indian Cultural Corridor. Initially looking to build a new space for their urban embassy, Red Lake Nation conducted research to ensure they were focusing on their urban band members’ top unmet needs. The research revealed that housing and healthcare were needed the most and that the majority of band members in the Twin Cities lived in the East Phillips neighborhood along Franklin Avenue.

Red Lake Nation’s research aligns with statistics showing that Native Americans face housing insecurity and homelessness at significantly higher rates than other groups in the U.S.—the result of centuries of systemic, forced displacement of Native Americans from their homelands. In the 19th century, the U.S. government established the reservation system to clear land of Native Americans for westward expansion and to attempt to eradicate Indigenous ways of life. Native Americans were forced to live in new areas and in new types of housing, and thousands of Native children were forced to attend Christian boarding schools.

Images 1–3: The apartments, embassy, and clinic have their own entrances. The embassy provides access to the community room, classroom, and childcare center. All photos by Alan Blakely.

A century later, the Indian Relocation Act of 1956 enticed Native Americans to leave reservations for urban areas, including Minneapolis, with tenuous and sometimes even fabricated promises of jobs and a “better life,” further weakening tribal communities. In the Twin Cities, the construction of Interstate 94 beginning in 1959 disrupted the community urban Natives had built in East Phillips.

“We don’t lack culture. We don’t lack spirituality,” says Olbekson, a member of the White Earth Band of Ojibwe and founder of Full Circle. “But when there are government strategies specifically designed to undermine us as a community and take away our economic structures and land, what is that going to do to any culture? It’s going to create this incredibly challenging situation.

“There are many ways that human beings cope with that kind of trauma,” he continues. “Dealing with that historical trauma—trauma that isn’t fully understood by those who haven’t experienced it or seen their own community experience it—is a major effort. It’s all tied to cultural revitalization.”

The community’s need for housing security was further reinforced in 2018 when the Wall of Forgotten Natives homeless encampment arose across the street from the Mino-Bimaadiziwin site. As winter approached, those working on the building project transitioned for a time to creating temporary navigation centers to provide shelter and services for those living in the encampment.

“There was support for [the Mino-Bimaadiziwin] project, but I wish more people would see that there’s a huge lost part of our [Native] community,” says Red Lake Nation tribal secretary Samuel Strong. “The system is broken. When the system isn’t serving the people that need help the most, then we should question the rules that are meant to help.”

“We talked to community members, the Red Lake Tribal Council, and others about reflecting the landscape of Red Lake. How do we bring that down into a building? How can we create that sense of warmth and nature in the context of a very urban site?”

Completed in 2021, Mino-Bimaadiziwin Apartments responds to community needs with living units large enough to accommodate multigenerational Indigenous families, which often include extended family members. The building, whose two wings shape a courtyard, is also home to the Red Lake Nation Embassy, a healthcare clinic, a childcare center, social services, community spaces, a playground, and a medicine garden, which is used by the clinic.

“The building’s program evolved over time,” says Cuningham architect Jeremiah Johnson, AIA. “We asked a lot of questions about the future use of the building, engaging as much as possible to make sure this building serves the community to the fullest extent.”

While the uses respond to the disproportionately high rates of housing instability and health issues in the Indigenous community, the design celebrates Red Lake Nation’s vibrant culture and traditions. Mino-Bimaadiziwin means “living a good life in balance with Indigenous values and being a good relative to the Earth and your community” in Ojibwe, says Olbekson. “We talked to community members, the Red Lake Tribal Council, and others about reflecting the landscape of Red Lake,” he continues. “How do we bring that down into a building? How can we create that sense of warmth and nature in the context of a very urban site?”

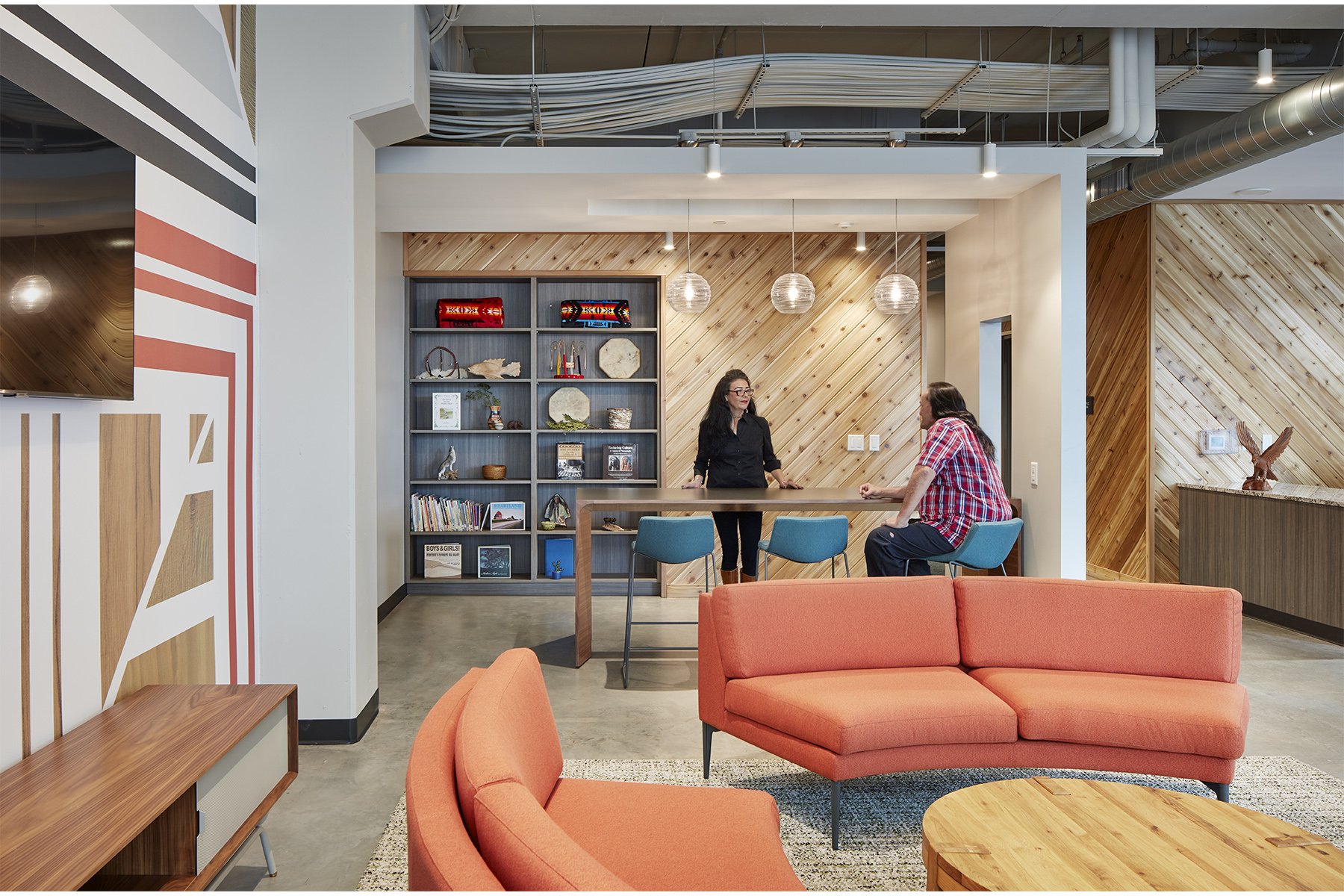

Images 1–7: Interiors like the entry lounge for the apartments respond to contemporary tribal life while honoring and communicating tradition. The Red Lake Nation Embassy (photo 4) is a hub for resident services, resources, and care. A pre-function area for the community room, classroom, and childcare center has direct access to the courtyard. Mino-Bimaadiziwin anchors the American Indian Cultural Corridor where it crosses Hiawatha Avenue and the METRO Blue Line. All photos by Gaffer Photography.

On the exterior, seven wood-tone elements that frame openings and entries are a subtle nod to the nation’s seven clans. Inside, the design team drew upon the clans and each of their associations for inspiration. The clinic interiors, for example, resonate with the Bear Clan, which is associated with defense and healing. Throughout the building, symbolism is similarly subtle and abstract, with materials, finishes, colors, and textures evoking the clans and the white cedar and birch of the Red Lake Reservation in northwestern Minnesota.

“We also specified plantings and trees that are native to the Red Lake Reservation and that also grow well here,” says Johnson. “It was important that key elements of the project relate back to home for the residents.”

“When you live here, you live in the context of culture,” says Olbekson. “You can practice your culture and participate in community. There are health services, community facilities, and childcare. It’s an environment that serves your needs in a comprehensive way as a person who would live in this community.”

That environment extends beyond the property lines with organizations and venues including the Native American Community Development Institute (NACDI), the Minneapolis American Indian Center, All My Relations Arts (AMRA), Little Earth Housing Corporation, the American Indian Opportunities Industrialization Center (OIC), and the Indian Health Board of Minneapolis. “The [Native] community doesn’t see this project and others in the corridor in isolation,” says Olbekson. “They are all part of us working together on everything from social services to recreation to jobs, and how we live as a community inside a very dominant community.”

“Mino-Bimaadiziwin is a little slice of Red Lake in the Twin Cities and a long-term asset for the tribe,” adds Strong. “I see it as an example of how we can begin to fill a huge need in our community and do it in a financially replicable way.”

“[Red Lake Nation] funded the whole process, and they asked a Native American architect to be integral to the design process,” says Olbekson. “A Native-owned contractor, Loeffler Construction, built the building. The Native American Community Clinic runs the clinic. There’s been so much opportunity for professional development and capacity building. In the spirit of self-determination and sovereignty, our community can say, ‘We did this.’ It’s a huge source of pride.”

The Mino-Bimaadiziwin project team included the Red Lake Band of Chippewa Indians, Cuningham, Full Circle Indigenous Planning + Design, BKBM Engineers, Emanuelson-Podas, Westwood, and Loeffler Construction.