Three Questions for LSE Architects, Winner of the 2023 AIA Minnesota Firm Award

LSE CEO Mohammed Lawal, FAIA, NOMA, and president Quin Scott, AIA, reflect on the impact that architects can have as designers, connectors, and neighbors

Interview by Chris Hudson | January 18, 2024

LSE Architects firm leaders Quin Scott, AIA, and Mohammed Lawal, FAIA, NOMA, in the firm’s new home—the top floor of the renovated Albinson Building in Minneapolis’s Harrison neighborhood. Photo by Andrea Rugg.

FEATURE

Sustaining and growing an architecture firm is a marathon, not a sprint. But LSE Architects is off to a swift start. Founded in 2011 by Mohammed Lawal, Quin Scott, and Ron Erickson as Lawal Scott Erickson Architects, the firm has grown from three people to 55 and from $200,000 in annual revenue to more than $17 million in just 12 years. LSE is now the largest Black-owned architecture and interior design firm in the Upper Midwest.

It’s also the recent recipient of a prestigious honor: the AIA Minnesota Firm Award, given biennially to a Minnesota architecture firm that has made outstanding contributions to the advancement of the profession.

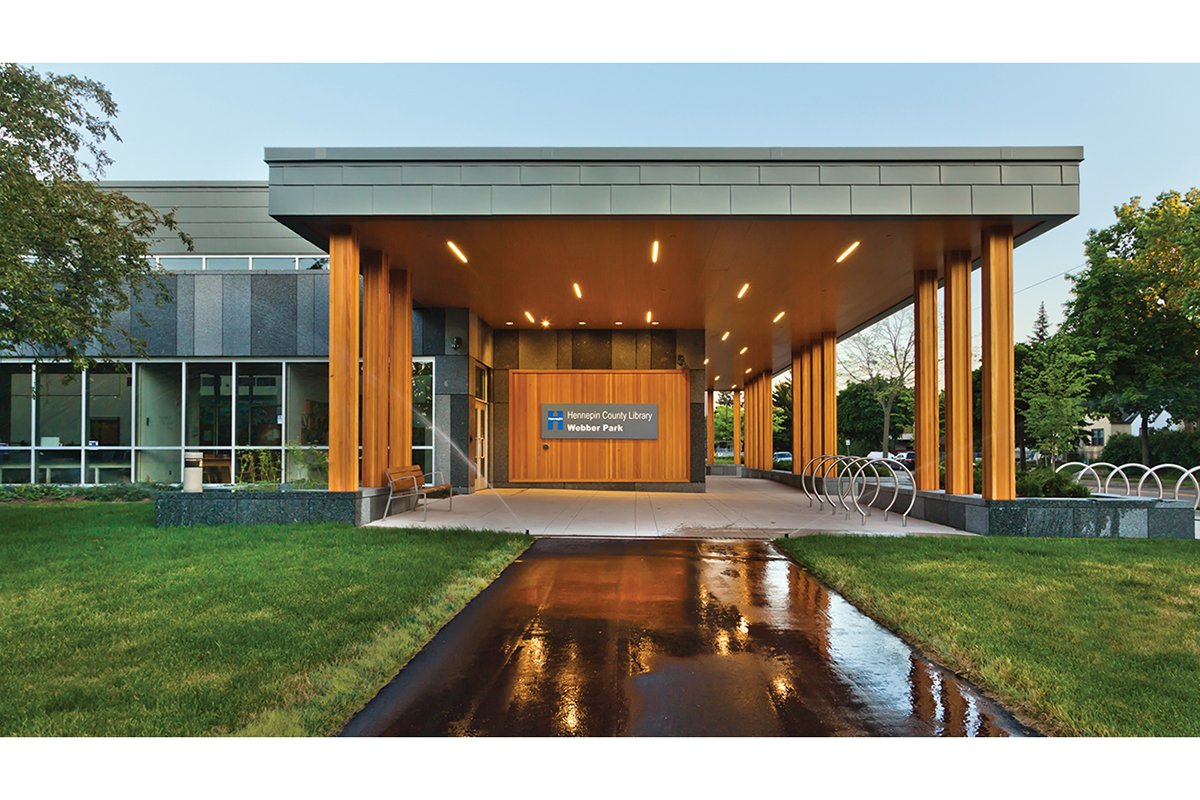

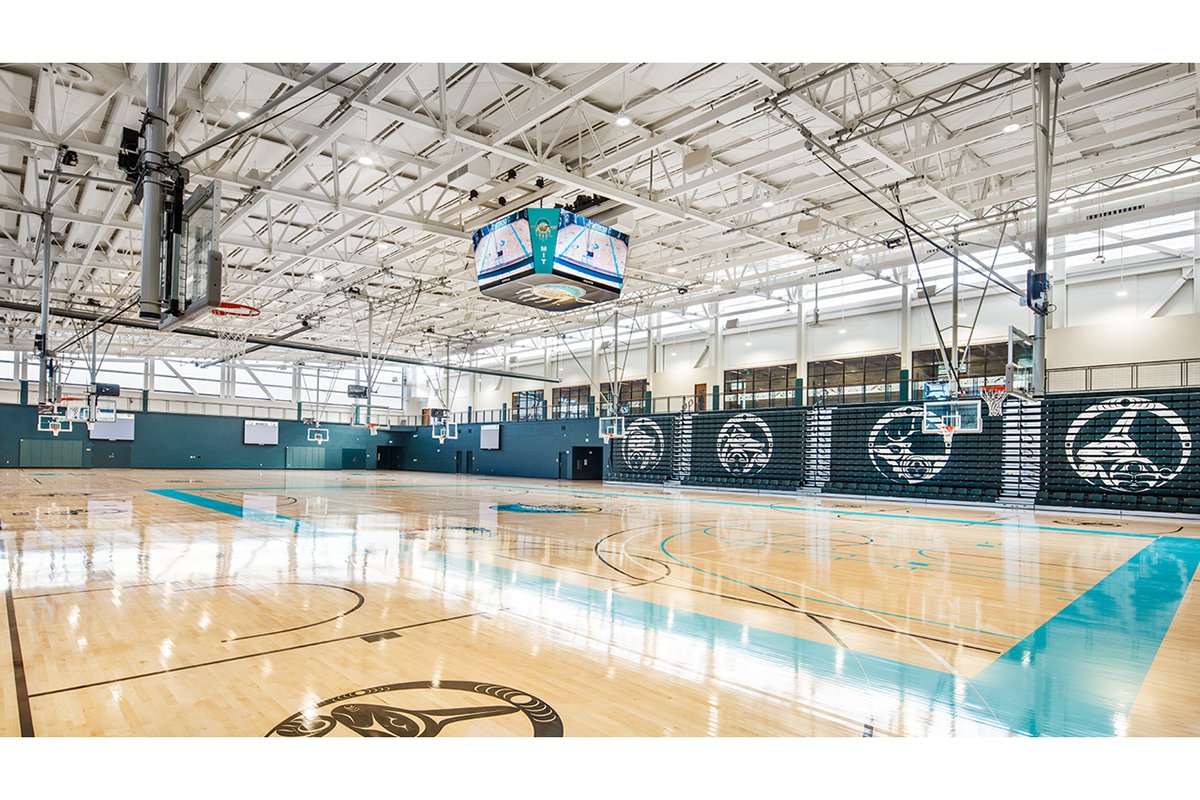

Over the past 12-plus years, LSE has expanded its expertise from tribal cultural and entertainment projects to schools, libraries, community centers, housing, and workplaces. Notable projects include a parking and office addition to Gillette Children’s hospital in St. Paul; Houston White Men’s Room, a commercial venture for entrepreneur Houston White in Minneapolis’s Camdentown neighborhood; and Satori Village, a mixed-use housing development in North Minneapolis for JADT Development Group’s Tim Baylor.

Along the way, the firm has built a reputation for drawing out insights and ideas from a wide range of project stakeholders, many of whom are meeting with architects for the first time. “Meet your clients where they are, and invite everyone to the table,” said Lawal in remarks made at the AIA Minnesota Awards Celebration in November. “Architecture is about building equity and access to good design, making it attainable for all, no matter where people live.”

“The projects they are most passionate about are often the most modest—but with the most community impact,” says Jennifer Yoos, FAIA, principal and CEO of VJAA and head of the University of Minnesota School of Architecture, who nominated LSE for the Firm Award. “These are projects where they used limited resources inventively, where they supported entrepreneurial activities, or where they changed patterns of working to create new and better models. This is both community building and sustainable design through the practice of architecture, and it is important work that benefits us all.”

ENTER sat down with Lawal and Scott in LSE Architects’ new studio in December.

Photos by Andrea Rugg

2023 was a big year for LSE Architects. In addition to receiving the AIA Minnesota Firm Award, you settled into a new studio in a building you purchased in Minneapolis’s Harrison neighborhood. What spurred you to invest in a new home?

Scott: When Ron, Mohammed, and I started the practice, we thought it would be nice to have a home someday that was ours, to better understand the development process, the city approval process, financing, and so on. Well, we got started probably six years ago now with a list of criteria for what we wanted in a building, including adequate space to have our whole team in one studio, flexibility to expand, and parking.

What drew us to this building [the 1968 Albinson Building on Glenwood Avenue] is that it’s in a community we’re working in. It’s in a community that’s underserved, in a development zone. We designed the Sumner Library addition nearby. We’re now working with the Link, an agency doing great work across the street. One way to understand the impact we can make on a community is to live in the community.

The net result is that we’ve got a nice place here that we can call home for a long time. The new studio has enabled an even more dynamic and collaborative work culture for our team. Our staff really likes this location. Our clients appreciate it, too—we’re able to open our office and conference rooms at times for clients to use for board meetings and other functions.

Mohammed, you often speak about the “currency game” in the context of LSE’s work.

Lawal: Recently, I was part of a panel discussion at Medtronic about generational wealth. There were three Black panelists: One person was in finance, another had started a business, and I was there as an architect entrepreneur. Even for the person in finance who had started a financial company, the idea of generational wealth was somewhat foreign to him as someone in the Black community.

“Meet your clients where they are, and invite everyone to the table. Architecture is about building equity and access to good design, making it attainable for all, no matter where people live.”

That’s because one of the things that’s grown generational wealth for a lot of families is real estate. Well, architects are in the real estate game. So, for me, being in that game allows us to start to help make connections between what it means to design, develop, and own real estate for yourself, your family, and your community, and how that can create value. That’s inherently what architects do. And that’s part of the currency game.

Unfortunately, there’s also a mindset [among architects and designers] that thinks, “We [just] design buildings. We’re not part of this other thing about equity in our community. We’re not part of the discussion on how the Twin Cities ranks second to last among the 100 largest metropolitan areas in the country in the income gap between White and Black households.”

We were able to purchase a piece of commercial real estate for the benefit of our company and the community. But I can tell you, I know a lot of people in my community who are not in the currency game. As architects, we need to elevate what we do by helping to make connections that bring more people into the game.

Photos 1–4: Recent LSE Architects projects include Hennepin County Library Webber Park, Minneapolis; Roseville High School renovation and addition; Regional Acceleration Center, Minneapolis; Muckleshoot Indian Tribe Community Center, Aubrun, Washington. Photos 5–8: The new Integrated Parking and Office Structure at Gillette Children’s. The ramp incorporates a covered playground with a “treehouse” that cantilevers out over the sidewalk. “It’s such an inclusive space,” says Beth Risberg, Gillette Children’s Vice President of Infrastructure. “Our young patients and their families can use it year-round, even when it’s raining or the snow starts to fly. It can be a space for physical therapy, too; our therapists can recommend activities for kids to do with their families or caregivers.” Gillette Children’s photos by Gilbertson Photography.

Scott: We can help each other out, build each other up. How do we get that opportunity for equity to the table? That’s part of our job as architects because we have that skill set and those relationships. Ron Erickson always talked about [the growth of] the tree—how branches spawn other smaller branches and the root system grows to create a stronger tree. We see that in the way we work with our clients and community partners.

If the founders of LSE Architects walked into this room from 2011 and were told the story of the firm’s first 12 years, what would they think?

Lawal: Well, if you had said to me in 2011 that in 2023 the firm would be recognized with the AIA Minnesota Firm Award, I would not have believed it. Even now, it’s still sinking in. We’re incredibly honored to be recognized by our peers for the body of work we’ve accomplished in a short amount of time, and for the ethos we bring to our work in the community.

But I think 2011 Mohammed would also say that we haven’t yet accomplished what we can in the community—that there’s a lot of work still to do. He would probably say, “I thought we’d be further along in terms of the currency game and the disparities in our community. I thought we’d be further along as architects.”

Scott: We’re focused on the impact we can make to try to help the Houston Whites and the Tim Baylors of the world create opportunities for their customers, or for their fellow investors. There are a lot of obstacles and roadblocks. The systems aren’t set up to support that work. You just need to be persistent. When one door closes, go on to the next. That’s kind of the core of our business.