Spotlight on University Grove

Six questions for architectural historian Jane King Hession on one of the most unique neighborhoods in Minnesota—and on the pioneering woman architect who left a lasting imprint on it

Interview by Chris Hudson | February 10, 2022

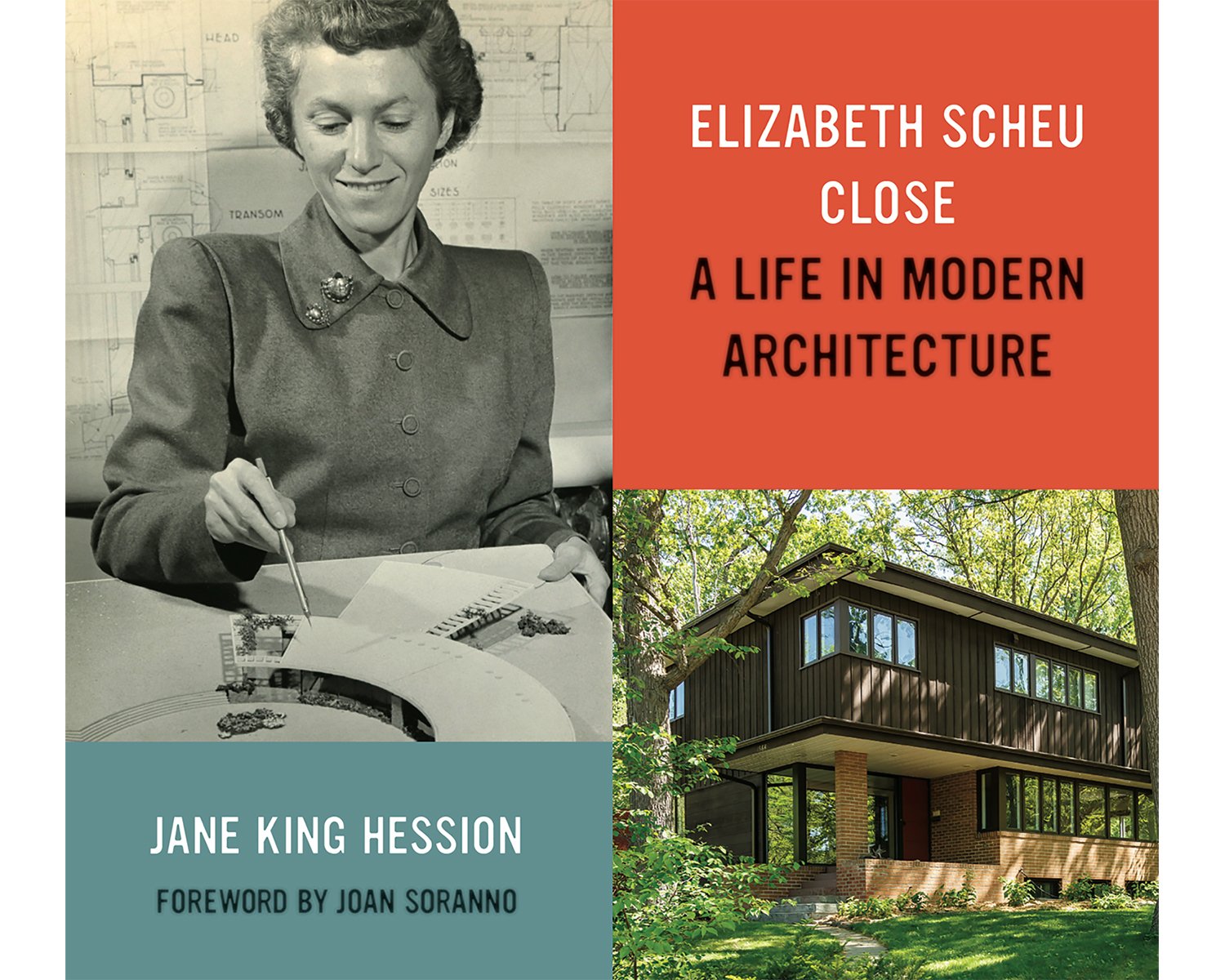

In 1953, architects Elizabeth and Winston Close designed a residence for their family in University Grove. Photo by William B. Olexy.

FEATURE

In the late 1920s, the University of Minnesota set aside gently rolling land in Falcon Heights, adjacent to its St. Paul campus, for the development of a residential enclave for university faculty and administrators. The idea was to attract top educators with the opportunity to build an architect-designed home on idyllic, university-owned land near campus—and it worked. Between roughly 1930 and 1970, University Grove slowly filled with 103 homes, first with Tudors and Colonials and then with an array of midcentury designs by Minnesota’s leading practitioners.

The U’s requirements that the homes be designed by architects and not exceed a moderate cap in construction costs translated to a collection of houses that are diverse in expression while compatible in scale. Nearly a century after it broke ground, University Grove remains a residential wonderland for lovers of midcentury design.

For insight on the Grove and its enduring appeal, ENTER spoke with Jane King Hession, architectural historian and author of Elizabeth Scheu Close: A Life in Modern Architecture. Elizabeth (“Lisl”) and Winston Close, founders of Close Associates, designed 15 houses in the Grove, including one for their own family. In the richly illustrated book, Hession traces the life of the groundbreaking architect from her childhood in Vienna in an architecturally significant home to her education at MIT and her seminal influence on modernism in Minnesota over a six-decade career.

Photo 1: The Shepherd House (1956), the first Ralph Rapson–designed home in University Grove. Photo by William B. Olexy. Photos 2–4: The Wolf House (1959), designed by Close Associates, was organized around a two-story interior court. Close Associates Papers (N78), Northwest Architectural Archives, University of Minnesota Libraries, Minneapolis. Photo 5: The Elliot House (1935), designed by Roy Childs Jones and Rhodes Robertson. Photo by William B. Olexy.

When did you first visit University Grove? What was that experience like?

I didn’t grow up in Minnesota, so I was unaware of University Grove until the late 1990s, when I began to research Ralph Rapson’s work for the exhibition and book Ralph Rapson: Sixty Years of Modern Design. I had the opportunity to walk the Grove with Ralph and tour several of the houses he designed there. It was immediately obvious to me that the Grove was a special place with a remarkable collection of residences in a range of styles designed by a Who’s Who of Minnesota architects. The New York Times said it best when they described the neighborhood as “an architectural time capsule.” I had never seen anything like it.

Elizabeth and Winston Close designed more homes in the Grove than any other firm, and they lived there themselves. Did Elizabeth embrace her close association with the place?

Ultimately yes, but initially she and Win were reluctant to build a home or live in the Grove as the social democrat in Lisl feared it might be “a company town,” by which she meant exclusionary. Instead, she found it to be a good place to live and raise children, and a “very successful neighborhood.” She and Win designed and built their home in the Grove in 1953, when Win’s faculty appointment made them eligible to do so. Members of the Close family lived in that house for more than 60 years.

“The New York Times said it best when they described the neighborhood as ‘an architectural time capsule.’ I had never seen anything like it.”

In Lisl’s opinion, a major strength of the Grove was the way it was platted to accommodate large, deep blocks. This allowed for common areas shared by all residents. She credited a cost cap, which limited the maximum amount that could be spent on the design and construction of a house, with making the Grove affordable for young faculty members, and as the reason why the similarly sized and scaled houses “don’t compete with each other.”

Is there an evolution—or any interesting surprises—in the Grove homes designed by Close Associates between the late 1930s and the mid-1960s?

All Close-designed houses in the Grove are modern, efficiently planned, and sited to respond to topography. Yet each is unique because every house was designed to provide for individual client needs—information that Lisl was meticulous about unearthing. The house I find to be most surprising and unusual is the 1959 Wolf House. Although it’s modern through and through, it was inspired by a Roman atrium house. According to Lisl, this ancient typology, which faces inward, solved the problem of a lack of privacy on the Wolfs’ site, which was flanked on two sides by streets. A two-story courtyard stands at the center of the Wolf House, around which all other rooms are arranged. It might not be the right house for everyone, but it suited subsequent owner Dudley Riggs, the late comedian and founder of Minnesota’s Brave New Workshop. His early training as a circus aerialist allowed him to change the light bulbs in the ceiling of the two-story atrium with the greatest of ease.

Images 1 and 2: The cover artwork for Elizabeth Scheu Close: A Life in Modern Architecture (University of Minnesota Press, 2020) includes a photo of the Tyler House, the Closes’ first project in University Grove; author Jane King Hession.

Which of the Close homes are standouts for you? Which other homes are favorites?

The Close House on Fulham Street is my favorite for personal and architectural reasons. I spent many hours in its warm wood interiors interviewing Lisl for a Minnesota Historical Society oral history project. It was interesting to talk to her in her natural habitat, as it were. I could experience certain design elements, like the no-nonsense kitchen, a space-saving spiral staircase, clever storage units, and the quality of light in the house as she described and demonstrated them for me. As her attention was often caught by the birds and wildlife outside the large living room windows to the rear of the house, I could fully understand how integral nature was in the plan of the house, and the importance of the inside/outside connection. The house is very modern in its simple, rectangular geometry and flat roof, but unlike many modern houses, it was placed to blend into the site and preserve trees. The horizontal redwood siding that wraps it resonates with the natural surroundings. There is an organic quality to the home that is not always found in modern design.

While I love modernism, I’m also very fond of the handful of Colonial houses in the Grove designed by Edwin Lundie. They, too, suit their sites especially well, and they tell us a lot about the kinds of houses architects were designing—and what clients wanted in a home—in the early 1930s. Another favorite is the Elliot House on Vincent Street, an early modern gem designed by Rhodes Robertson and Roy Childs Jones in 1935. What I like most about the house is the way it prefigures the wave of European modernism that would soon sweep across the country. Considered together, these homes offer a wealth of architectural historical insight within a couple of blocks.

Video: View a Docomomo short featuring a home in the Grove designed by noted architect Tom Van Housen, who recently passed away.

What should design enthusiasts taking their first stroll through the Grove look for in terms of important planning and design features?

The first thing design enthusiasts should notice is that University Grove is laid out not on a rigid grid but on a relaxed one that allows for some curving streets and the rise and fall of the land. This makes walking in the Grove a very pleasant experience. They will also notice that there are no walls or fences that cordon off individual properties; instead, a sense of community ownership and shared land is stressed.

Walking from west to east in the Grove is both a chronological journey and a stylistic one. The westernmost portion is the original and oldest section of the Grove. It comprises 66 houses, including the first house, built in 1929. Period styles prevail in this section—with the exception of the Closes’ modern designs. Sharp-eyed strollers will note that there are fewer two-car garages in this segment, as they were not permitted in the Grove until the 1950s. Beginning in the 1960s, an additional 37 houses were built to the east, with the last house constructed in 1970. Homes in this part were designed by the Closes, Rapson, Carl Graffunder, Robert Cerny, James Stageberg, and Michael McGuire, among others, and they reflect the evolving sensibilities of modern and contemporary architecture.

Why, despite its mix of design styles, does the Grove feel cohesive?

Although it might seem unlikely that a neighborhood of more than 100 houses built over a 40-year period by an eclectic group of architects would feel like a cohesive enclave, indeed the Grove does. A primary reason for this is that all the houses were designed by registered architects; therefore, the quality of the architecture is extremely high. Each house is unique, but together they form an unparalleled collection of the work of Minnesota’s most accomplished residential architects of the period.

Purchase Elizabeth Scheu Close: A Life in Modern Architecture from an independent bookstore near you.