Gathering Spaces by Edward Sövik

The design philosophy of the midcentury Northfield architect through the lens of two of his hometown projects

By Frank Edgerton Martin | August 31, 2018

The late Edward Sövik seated in Christiansen Hall of Music’s Urness Recital Hall. His design for this light-filled space fused festive atmosphere with a deep sense of spirituality. Photo courtesy of the St. Olaf College Archives, Northfield, Minnesota.

FROM THE ARCHIVES

Noted church architect Edward Sövik Jr. believed that people, not architecture, make spaces sacred. He viewed Christianity as rooted in charity and believed that simplicity in design and materials best expressed this value for spaces focused on the Christian act of gathering. In the decades after World War II, Sövik developed a humane modernism for worship and performance that resonated nationwide—nowhere more so than in Northfield, Minnesota, where he practiced for a half-century. ENTER looks back at his remarkable life and career.

Student, War Hero, Architect

Born in Henan Province in China to Lutheran missionaries in 1918, Sövik first came to Minnesota to attend St. Olaf College along with his twin brother and older sister. After graduating from the school in 1939, he enrolled as a painting student at the Art Students League of New York, where Jackson Pollock, soon to be a major figure in the Abstract Expressionist movement, had recently studied. During World War II, Sövik served as a Marine Corps fighter pilot in the Pacific and was awarded a Purple Heart and a Distinguished Flying Cross.

After the war, Sövik earned an architecture degree from Yale University and returned to Northfield to establish his practice—today’s SMSQ Architects—and teach art at St. Olaf. For the next 50 years, he helped lead the modern movement in Protestant church design and shaped dozens of religious and academic buildings across the country. He died in 2014 at the age of 95.

“Ed saw himself as bringing the concepts and principles of modern architecture to church design,” says SMSQ Architects’ Pepe Kryzda, AIA. “He was very confident about the work he was doing.”

“He was firm in his ideas and his trajectory, but he was always soft-spoken,” adds SMSQ’s Gary Johnson, AIA, who worked with Sövik for more than a quarter-century.

Sövik was also a superb writer, contributing to Architecture MN and dozens of religious journals and conferences. His small book Architecture for Worship, published in 1973, is the most complete and influential summary of his thinking. It still sounds radical today. “Jesus, as everyone knows, didn’t ask his followers to build anything,” he wrote in the opening page. “Worship involves persons, not places. Persons are the temples. They are the holy things.”

Sövik argued that the idea of Christian architecture had taken an historic detour beginning in the Age of Constantine in the fourth century. From Byzantine to Romanesque to High Gothic, the eras of rarified and grandiose church architecture continued for 1,600 years.

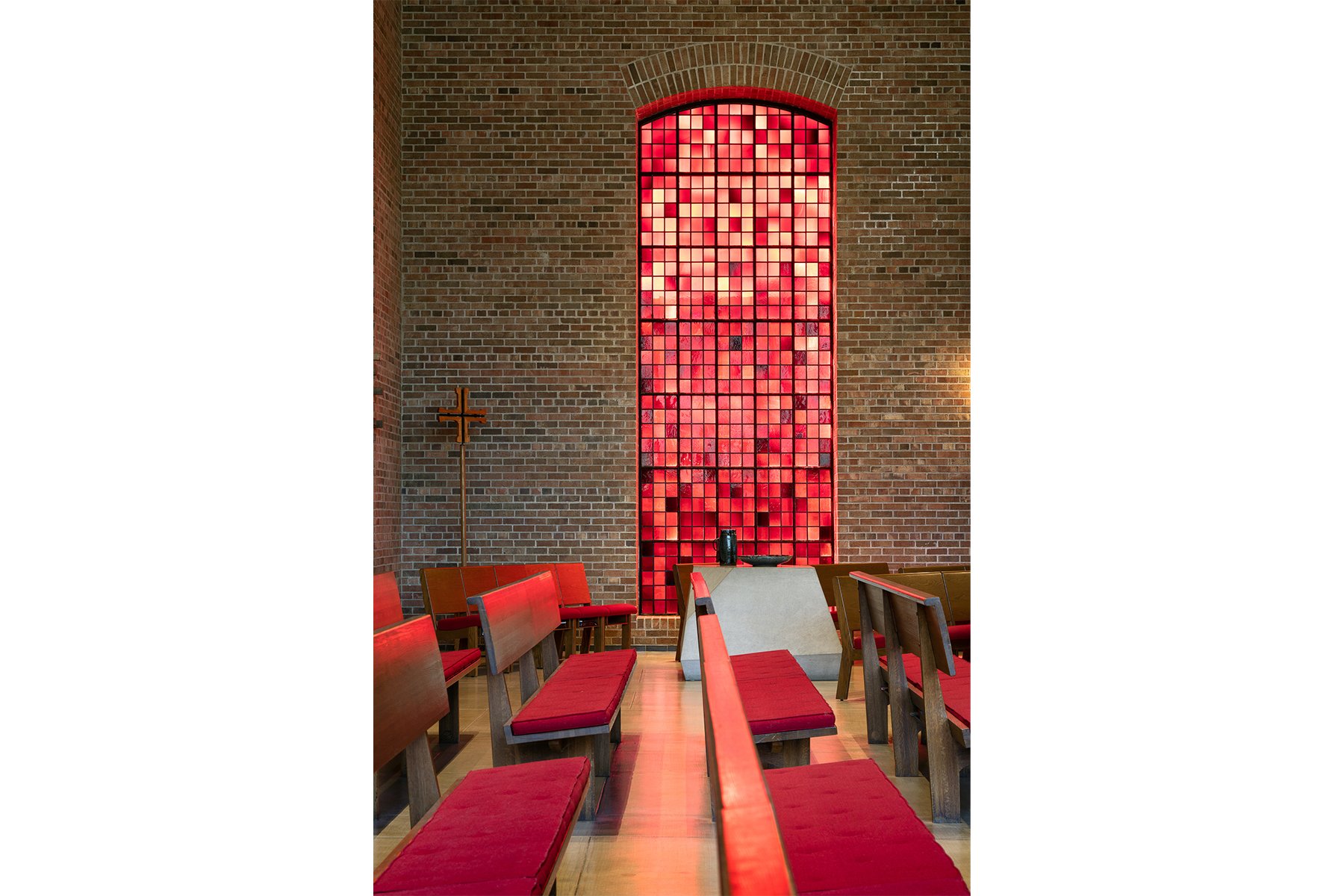

Images 1–6: Northfield United Methodist embodies Sövik’s belief in the “single-space church”—the idea of a unified body of believers and not an audience watching a performance. A single, soaring stained-glass window on the south wall creates a warm red glow. The 12 “Apostle windows” illuminate the sanctuary with a soft northern light. Photos by Peter J. Sieger.

Northfield United Methodist Church

In 1964, when Northfield United Methodist Church commissioned Sövik to design a new home for its congregation on the southern edge of town, the architect wrote a series of 12 “Reflections” on the new design for the church’s monthly newsletter. In the third reflection, “The Presence of God,” Sövik wrote that the “most important things in the church are not the communion table, the font, the cross, or the pulpit, but the people.” The focus, he explained, shouldn’t stay on one element or person; it should shift from one space to another, and “sometimes the whole body of believers will be the real center of attention.”

When you enter the sanctuary today, that sense of fluidity and gathering fills the room. More cubic than linear, the space receives daylight from three sides; a four-point wooden Roman cross stands amid the pews. The altar can be moved and, depending on the time of day and season, the sunlight and shadows change, too.

“The worship space is a classic Sövik ‘centrum’—a multipurpose, square, open room without a single, fixed focal point,” says scholar Gretchen Buggeln, author of The Suburban Church: Modernism and Community in Postwar America (2015). “Sövik designed it to be flexible and accommodating for the various worship needs of the congregation. He believed that honesty in design and materials—simplicity and straightforwardness in plan, structure, and finish—was the proper expression of Christian belief, but the brick, wood, and stone he used here are beautiful, high-quality materials.”

“Sövik believed that honesty in design and materials—simplicity and straightforwardness in plan, structure, and finish—was the proper expression of Christian belief.”

“My first impression of the sanctuary was that it was a very distinctive space, but I wasn’t sure how to navigate it,” says Jerad Morey, Northfield Methodist’s associate pastor. “Now, I appreciate that there is space to walk around during the service—and not designated spots for different moments. I can achieve intimacy with the congregation just by walking down a few steps from the altar.”

Morey also describes the glow when light streams through the 12 “Apostle windows” behind the choir area. “Some of the best moments,” he says, “are when you can see the snow on the trees outside the Apostle windows shining bright white against the blue sky.”

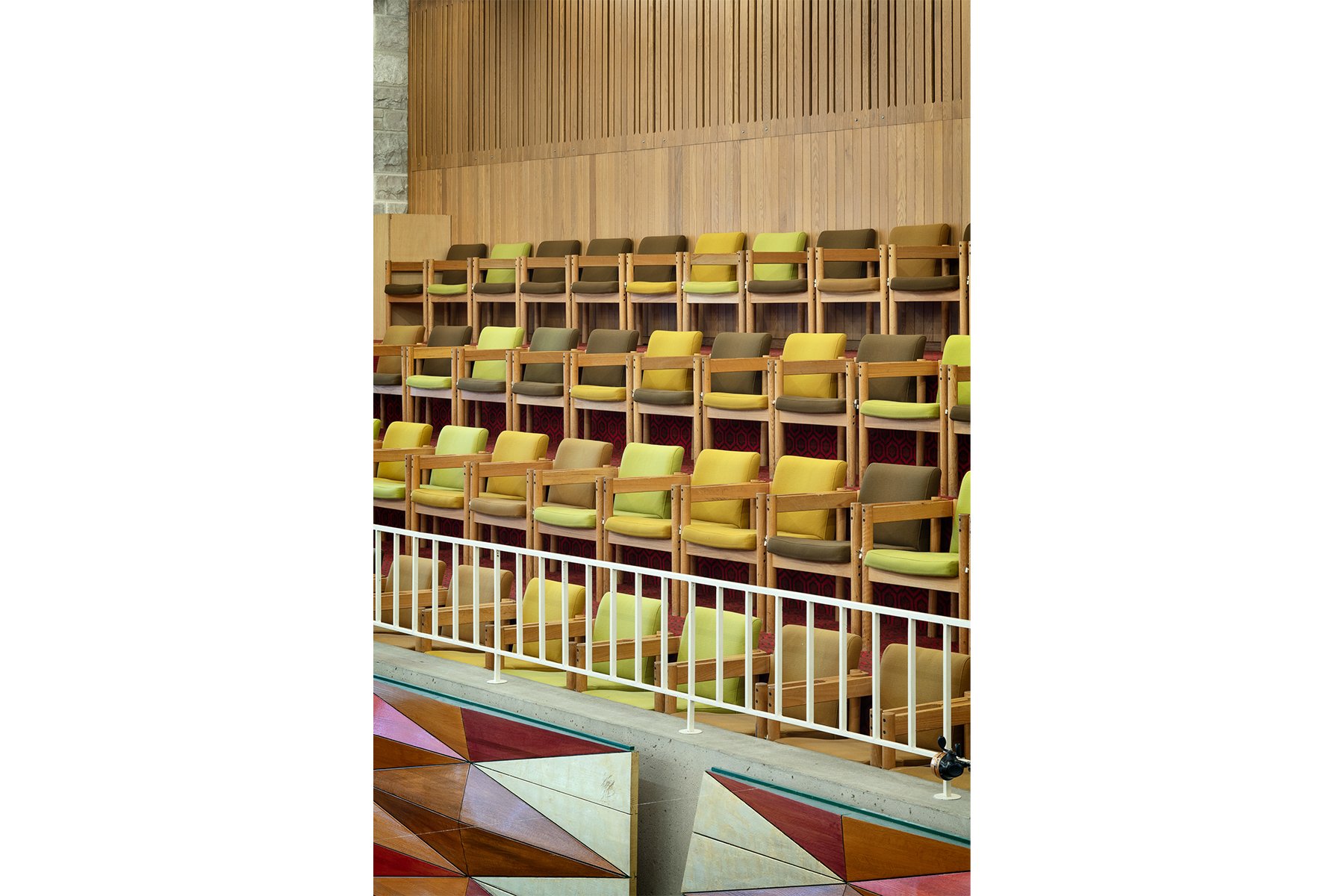

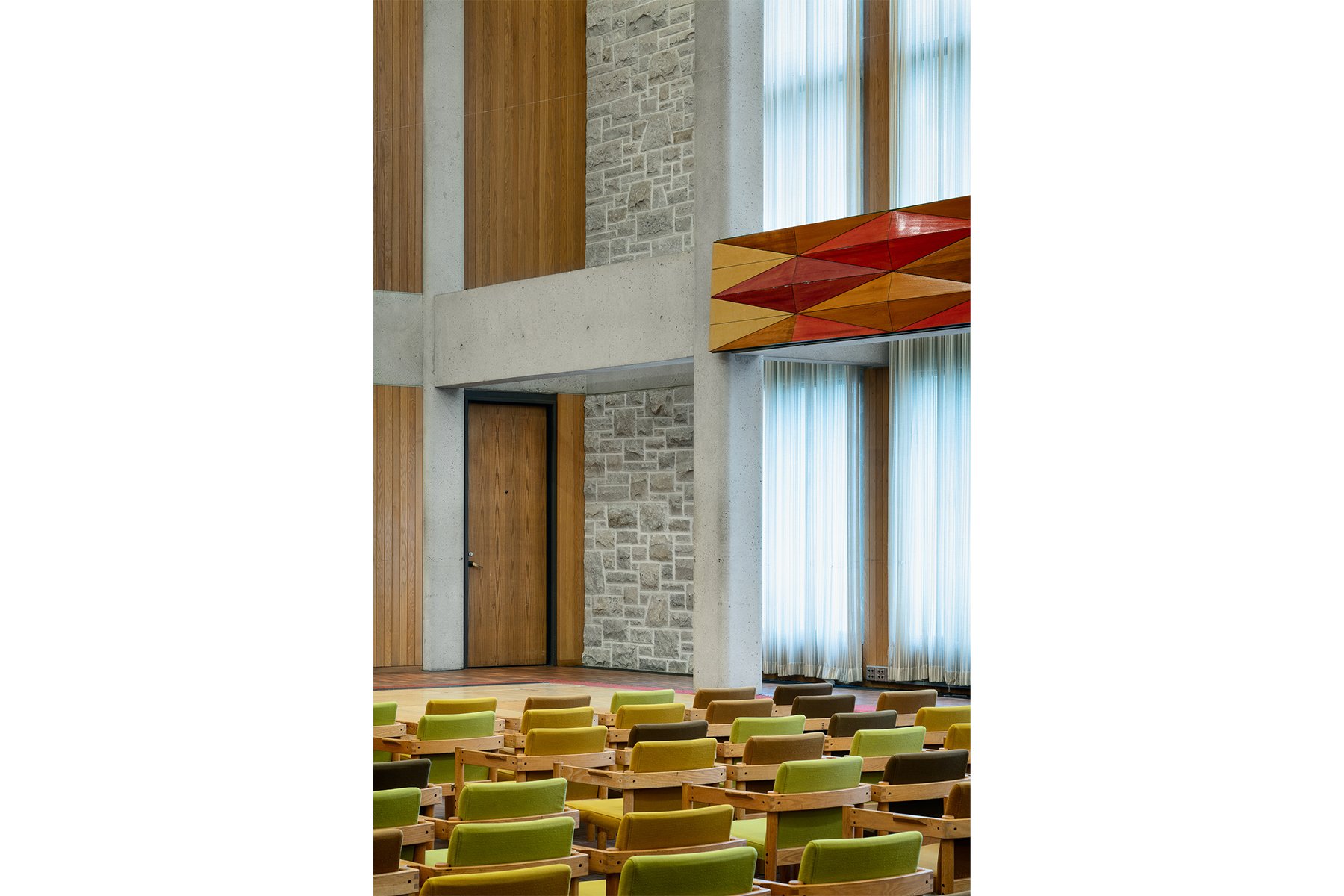

Images 1–7: Connected in pairs and upholstered in a complementary set of colors, the Sövik-designed “St. Olaf Chairs” in Urness Recital Hall are easily rearranged to reconfigure the audience and create subtly different confetti patterns. Outside, Christiansen Hall of Music’s west elevation expresses Sövik’s humble, finely crafted modernism. Photos by Peter J. Sieger.

Urness Recital Hall, Christiansen Hall of Music

Anton Armstrong, Tosdal Professor of Music at St. Olaf College and conductor of the school’s celebrated choir since 1990, has a personal attachment to Sövik’s architecture. “The college broke ground on Christiansen Hall of Music the first day of my freshman year, in 1974,” he recalls. As a nationally renowned choral music teacher, Armstrong travels widely for concerts and workshops at colleges and churches. “But over the last 30-plus years,” he says, “every time I come back here, I have a renewed appreciation for Christiansen and the Urness Recital Hall.”

Like Northfield Methodist, Urness Recital Hall is a large yet intimate room filled with light from a bank of north-facing windows. With balconies on two sides, the space seems to wrap around the performance stage, once designed to be mobile but now more or less permanently located at the hall’s western end. In the playful spirit of the 1970s, Sövik illuminated the space with hundreds of globe lights lining the balconies and the ceiling grid. He also designed wooden attachable chairs that could be arranged to meet performance needs.

“I heard a story—I can’t vouch for its accuracy—that, since Sövik entered the competition for the rebuilding of the chapel at his alma mater and didn’t win with his contemporary design, Christiansen was really his ‘chapel’ for St. Olaf,” says Buggeln. “It is a lot like his worship spaces: perfect acoustics, beautiful materials, elegant simplicity—a serene and peaceful space.”

In a 2018 Architecture MN interview, then music professor and associate dean Kent McWilliams pointed to the frequent and varied use of the hall, which hosted more than 100 recitals that year. “Guests to campus regularly compliment us on the fine aesthetic quality of the space,” he added. Urness also houses practices for St. Olaf’s beloved Christmas programs, when up to 465 students pack into the main floor and balconies to rehearse.

Sövik’s restrained material palette appears throughout the building, which won AIA Minnesota’s prestigious 25 Year Award in 2003. In the foyers and hallways, brick floor pavers, exposed concrete columns, and contoured wood ceilings create a sense of tactility and warmth while also expressing the heavy structure necessary for sound insulation. There are dozens of private practice rooms and rehearsal spaces of varying sizes.

Armstrong notes that, nearly 50 years after opening, Urness still has very good acoustics, with great clarity for the spoken voice. “There is a basic grandeur and beauty in that room,” he says. Even during a rehearsal with only a few performers, the feeling is one of gathering and shared purpose. The architect’s legacy lives on.