Housing First at Higher Ground St. Paul

The winner of the 2020 Affordable Housing Design Award is designed to create a path from emergency housing to permanent supportive housing and beyond

By Cinnamon Janzer | March 18, 2021

Higher Ground St. Paul entrance on West Fifth Street. Photo by Farm Kid Studios.

FEATURE

LHB architect Todd Rhoades, AIA, specializes in affordable housing and is fueled by a belief that everyone should benefit from good design. He especially loves working for the clientele, which includes residents and passionate housing organizations that develop and support the projects. But the work isn’t without its challenges. “It’s rare to succeed in competing with other developers in the search to find really great sites for affordable and supportive housing,” says Rhoades.

Count Higher Ground St. Paul as a win for supportive housing—and for the city. With its high-profile downtown location and award-winning design, it joins other innovative housing efforts in Minnesota in raising the bar for what shelter and supportive housing can be and provide.

Outside and inside Higher Ground St. Paul, the first phase of the two-phase Dorothy Day Place. Photos by Farm Kid Studios.

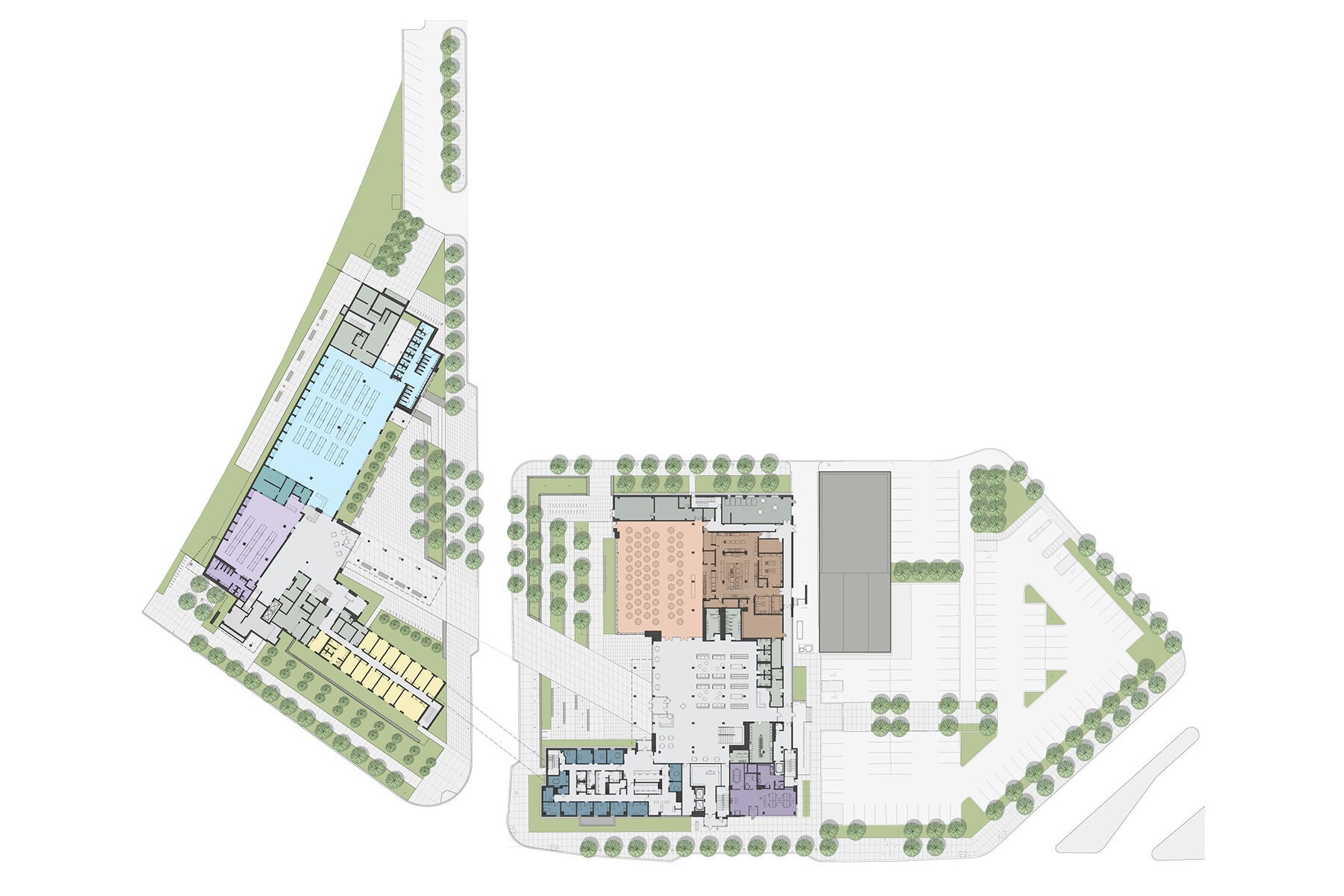

Opened in January 2017 as the first phase of the two-phase Dorothy Day Place, Higher Ground St. Paul combines emergency shelter, long-term stays, and permanent supportive housing. It’s now paired with the St. Paul Opportunity Center and Dorothy Day Residence (phase 2) across the street to provide everything from social services and storage lockers to barbers in one place. Run by Catholic Charities of St. Paul and Minneapolis and executed in partnership with the City of St. Paul, Dorothy Day Place is the largest public-private social-services partnership in the state’s history.

“It was really important that we create a dignified shelter,” says Tracy Berglund, Catholic Charities’ senior director of housing stability. That emphasis is evident in Higher Ground’s details. “We added custom ports and places to plug in a computer and cell phone into each bunk,” says Berglund. “The residents are trying to connect with family and employment, and they have technology that’s needed to make those connections.”

Noise-reducing acoustic panels in the shelter are another important feature. “We were mindful about the noise because trauma-informed care is very important to us, knowing that our folks have experienced a lot of trauma in their lives,” says Berglund. Expanses of wood ceiling throughout the five-floor building help minimize noise as well, while also lending visual warmth and welcome to the large entry lobby, Berglund adds.

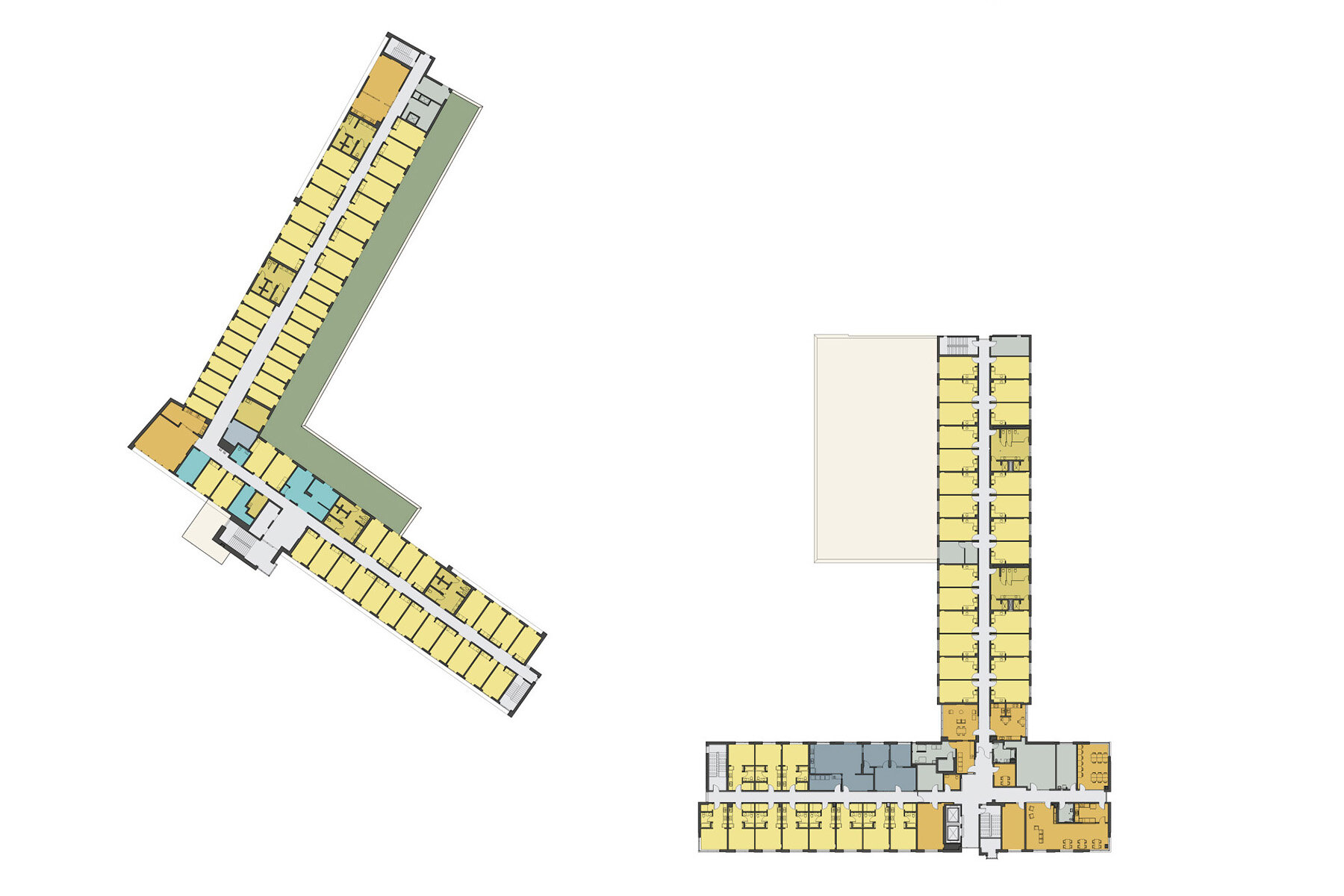

The idea is that the movement of residents from the lower to the higher floors is a physical representation of their personal ascension toward more stability in their lives. Some of the residents are finding consistent housing for the first time in decades.

Outside, the building seamlessly integrates into the city that surrounds it. “People experiencing homelessness have to feel like the city is their home,” says Rhoades, who led the project for Cermak Rhoades Architects, which was acquired by LHB in 2019.

Sited on a triangular plot of land just blocks from the Xcel Energy Center, the Mississippi River, and the city’s central business district, the L-shaped building boasts views of the State Capitol and St. Paul Cathedral. “Higher Ground St. Paul holds its own within the context of these iconic buildings,” says Rhoades. “It’s positioned as a welcoming gateway into downtown.”

On the grounds themselves, the building features a generous courtyard and green roofs designed to ease the transition from outside to inside for residents who are often accustomed to spending time outdoors. It also features plenty of natural light indoors. A heated-concrete walkway at the entrance minimizes the need for snow removal while keeping residents, particularly those with walkers, safe in the winter.

Because the building sits on rising land between the downtown business district and Cathedral Hill, its design quality can be seen from a distance. “If you drive by, it looks like a modern apartment building—and that was intentional,” says Tim Marx, the former CEO of Catholic Charities of St. Paul and Minneapolis, who helped shepherd the project into being.

But perhaps Higher Ground St. Paul’s most impactful feature is the arrangement of the housing options it contains.

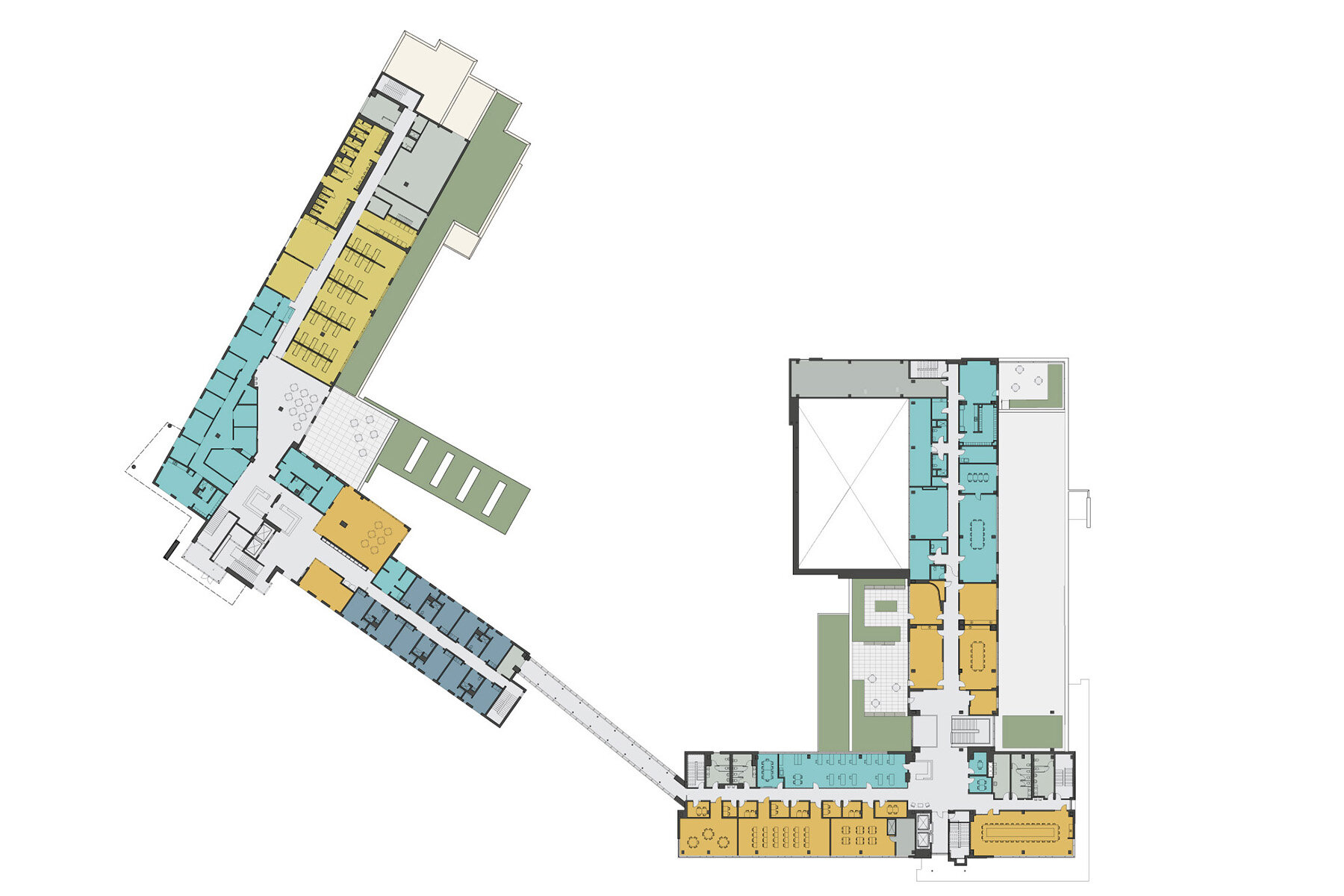

Men’s and women’s overnight shelters and late-stage alcoholic housing are located on the first floor. On the second floor are medical respite housing and, for men, a pay-for-stay shelter that costs $7 a night or $42 a week, which Catholic Charities saves for residents to eventually put toward a security deposit on an apartment, or first month’s rent. The top three floors contain 193 permanent homes for men and women in the form of single room occupancy and pod housing.

The idea is that the movement of residents from the lower to the higher floors is a physical representation of their personal ascension toward more stability in their lives. Some of the residents are finding consistent housing for the first time in decades.

Outside and inside the recently completed St. Paul Opportunity Center and Dorothy Day Residence, the second and final phase of Dorothy Day Place. Photos by Farm Kid Studios.

The concept of residents transitioning upward through the building came from the first Higher Ground, a smaller facility that Catholic Charities opened in Minneapolis in 2012. What’s new about the St. Paul campus is its significant scaling up of the model.

“We truly copied ourselves,” says Berglund. Catholic Charities had the idea to put housing above the shelter in Higher Ground Minneapolis after noticing a missing link between shelter and independent housing—especially in the context of the Twin Cities’ squeezed affordable-housing market. The concept worked, so they replicated it in Higher Ground St. Paul and added to it with the recently completed St. Paul Opportunity Center.

That second phase of the project brings an array of social services to Dorothy Day Place, from physical, mental, and chemical-dependency health care services to employment training. Clients are also able to access assistance with housing searches; veteran’s, SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program), and medical benefits; and financial and legal help, alongside a nutritious meal, a shower, and laundry options.

While the pandemic has impacted the number of people Higher Ground St. Paul can house and serve, Catholic Charities is ready to ramp capacity back up as soon as they are able.

“As we come out of COVID, we have to continue to use Higher Ground and other housing-type models to get up to speed, scale, and intensity and bring more housing online cost effectively, so that we don’t continue to rely on shelter, which is intended to be a temporary solution,” Marx explains.

Catholic Charities’ focus on lasting solutions reflects a larger shift over the past decade toward the Housing First approach to assisting people who are experiencing homelessness.

“We shape our buildings, and they shape the whole person and the whole community,” Marx says of the organization’s ethos. Providing beautiful and dignified housing, he says, helps “people who have been affected by structural racism, hunger, chemical and other substance abuse, and other kinds of underlying trauma to have more hope in their lives.”

The Higher Ground St. Paul project team included Catholic Charities of St. Paul and Minneapolis, Cermak Rhoades Architects (now with LHB), Watson-Forsberg Company, Coen + Partners, Mattson Macdonald Young, Emanuelson-Podas, and Pierce Pini + Associates.