Duluth Embarks on an Effort to Restore Its Embattled Shoreline

The City of Duluth and LHB prepare to implement a resiliency plan for the Lakewalk and Brighton Beach

By Justin R. Wolf | August 25, 2022

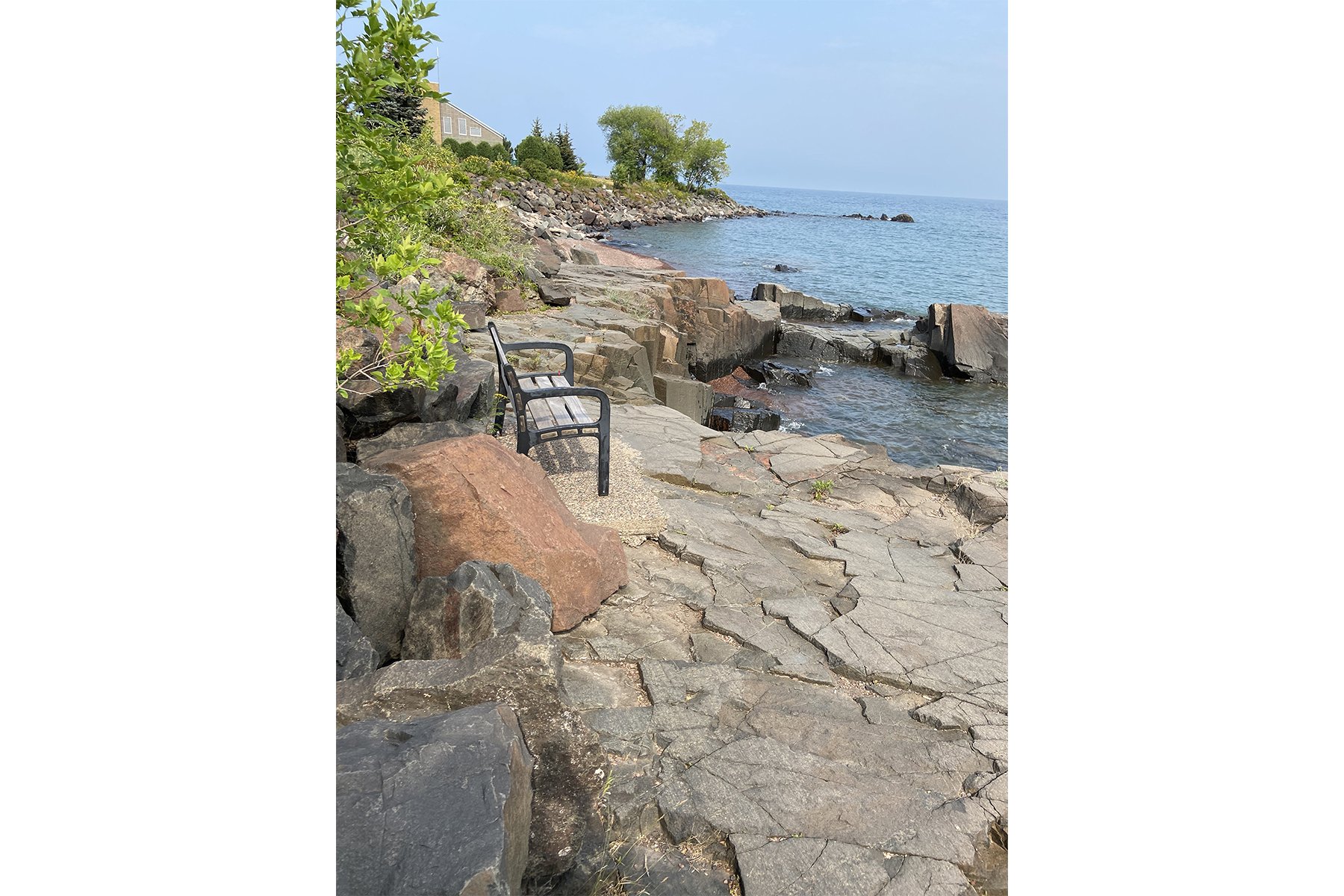

The Lakewalk at Fitger’s Inn, a short walk up the shoreline from Canal Park. Photo courtesy of LHB.

FEATURE

At the western tip of Lake Superior, Duluth, Minnesota, is the world’s most inland port, with heavy freight activity along its rocky shores. It draws an average of 6.7 million tourists each year, many of whom get at least a taste of the city’s 370 miles of trails. Duluth is also a particularly long city. It boasts 16.9 miles of lakeshore, which is a little more than half the length of the city’s linear span (the rest hugs the St. Louis River to the south). Neighborhoods like Kenwood and Chester Park slope toward the shore and contain several intersecting creeks that all flow into the lake. There’s just no escaping the water in Duluth.

There’s also no escaping the immensely powerful impacts the Great Lake has had on the land over time. Even glimpses of the shoreline have a way of opening eyes to preceding millennia.

“Geologically, this is a young lake. The land hasn’t found where it wants to be in equilibrium with this big body of water,” says Jim Shoberg, a senior parks planner and landscape architect with the City of Duluth. Indeed, today’s lakeshore was once under several hundred feet of water. When glaciers retreated after the last ice age, more than 10,000 years ago, the shoreline was roughly where Skyline Parkway is today. “Europeans came in and decided they knew where the shoreline was,” says Mike LeBeau, the city’s construction project supervisor. “They built roads and buildings on it, not yet understanding that it was temporary.”

Photos 1–8: Shoreline with native vegetation; shoreline at Fitger’s Inn; Brighton Beach restoration; Brighton Beach storm waves; kids at play; Lake Superior coastal forest; rocky shoreline with bench; gabbro bedrock shoreline. Photos 1–3 courtesy of AMI Consulting Engineers. Photo 4 courtesy of Duluth News Tribune. Photos 5–8 courtesy of LHB.

LeBeau and Shoberg are key players in the city’s efforts to rehabilitate its coastal infrastructure, including Duluth’s beloved Lakewalk, a nearly eight-mile paved trail that stretches from Bayfront Park to Brighton Beach (Kitchi Gammi Park). In the past decade, high-water records and storms with hurricane-force winds have occurred with greater frequency, fueled by climate change. “When the lake gets full and the wind blows, it tears the shoreline up,” says Shoberg.

“In certain areas of high wave action, it’s evident that a good 10 to 12 feet of shoreline has eroded,” says Heidi Bringman, a senior landscape architect with architecture and engineering firm LHB, which provides integrated restoration strategies to the city. “We can’t build that back.” Bringman adds that it isn’t only the lake that shapes shoreline conditions. Before the very first half-mile stretch of Lakewalk was paved, in 1986, the shore “was a dumping ground,” she says. Old railroad ties, scrap metal, car parts, and concrete waste from old sidewalks were just some of the toxic detritus clogging up the shoreline. When I-35 was extended through Duluth in the early 1980s, tons of earth from newly excavated tunnels were diverted to the lakeshore as well.

The cleanup that accompanied the creation and expansion of the Lakewalk was far from a concerted effort to restore the shoreline to its natural state. “It wasn’t engineered to standards you see today,” says Shoberg. “The infrastructure was built too close to the lake.” Pedestrian traffic and the formation of unsanctioned trails—more than 100 miles of them—compacted the soil, while the introduction of invasive, non-native flora—a byproduct of turning the lakeshore into a dumping ground—further allowed lake seiche to degrade embankments along the shore. “People often phrase [the work we’re doing] as ‘repairs to the Lakewalk,’ but what we lost was acres of earth that happened to hold the trails,” says LeBeau.

The plan that LHB is developing for the Lakewalk and for Brighton Beach, at the north end of the trail, has many layers and stages, but it is essentially twofold: Retreat from the lakeshore and “re-wild” the landscape. The former is a matter of thoughtful realignment. Trail-goers can be educated with new signage and directed to expansive overlooks, or “pause areas,” that are equipped to handle large numbers of visitors. Closing off the informal trails, on the other hand, is no easy feat. “When people want access [to the lake], they do things that aren’t great for natural systems,” says Bringman.

The plan that LHB is developing for the Lakewalk and for Brighton Beach, at the north end of the trail, has many layers and stages, but it is essentially twofold: Retreat from the lakeshore and “re-wild” the landscape.

The re-wilding of the shoreline with native plants will be an exercise in patience, after decades of abuse and neglect. The dense forest abutting Brighton Beach will be left “to take back some of the landscape,” says Shoberg. “Wherever there is an opportunity to reintroduce deep-rooted, fibrous material that’s native to the North Shore, we’re going to do that.”

In LHB’s plan, four native plant communities once deemed “threatened” in the region will soon find their way back to Duluth’s shores: white cedar, North Shore spruce-fir woodland (balsam fir, white spruce, paper birch, and black spruce), Lake Superior bedrock shrubland (various shrubs, wildflowers, sedges, lichens, and more), and woody shrubs for slope stabilization including willows, dogwoods, and wild rose. “The re-wilding will bring back that diversity and the natural ecological buffer,” says Bringman.

Construction will begin at different locations in 2023. The plan for the renewal of the Lakewalk and the resiliency of Brighton Beach won a 2022 Honor Award from the Minnesota chapter of the American Society of Landscape Architects. LHB received the 2021 AIA Minnesota Firm Award, in large part for its longstanding commitment to sustainable design and climate change research.

Whether the retreat and re-wilding are viewed as an exercise in protecting the city from the lake or an attempt to achieve balance with the forces of nature, a more resilient Duluth is in everyone’s interest, including that of wildlife. Restoring and protecting a diversity of flora will also invite a diversity of fauna. Deep-rooted shrubs and other native plant life will not only stabilize and protect the lakeshore but also protect animals from foot traffic and other unwelcome incursions.

“All across town, we’re trying to bring back the species that are supposed to be here, to support the wildlife that use Duluth as a [migration] corridor,” says Shoberg. “Bird species that come through need safe stopovers all along the way. If [they] come in and get a meal of buckthorn or Tatarian honeysuckle, they’re going to die over the cornfields of Iowa.

“Things are a bit wilder up here, and our outdoor spaces reflect that,” he continues. “Nothing is static.”